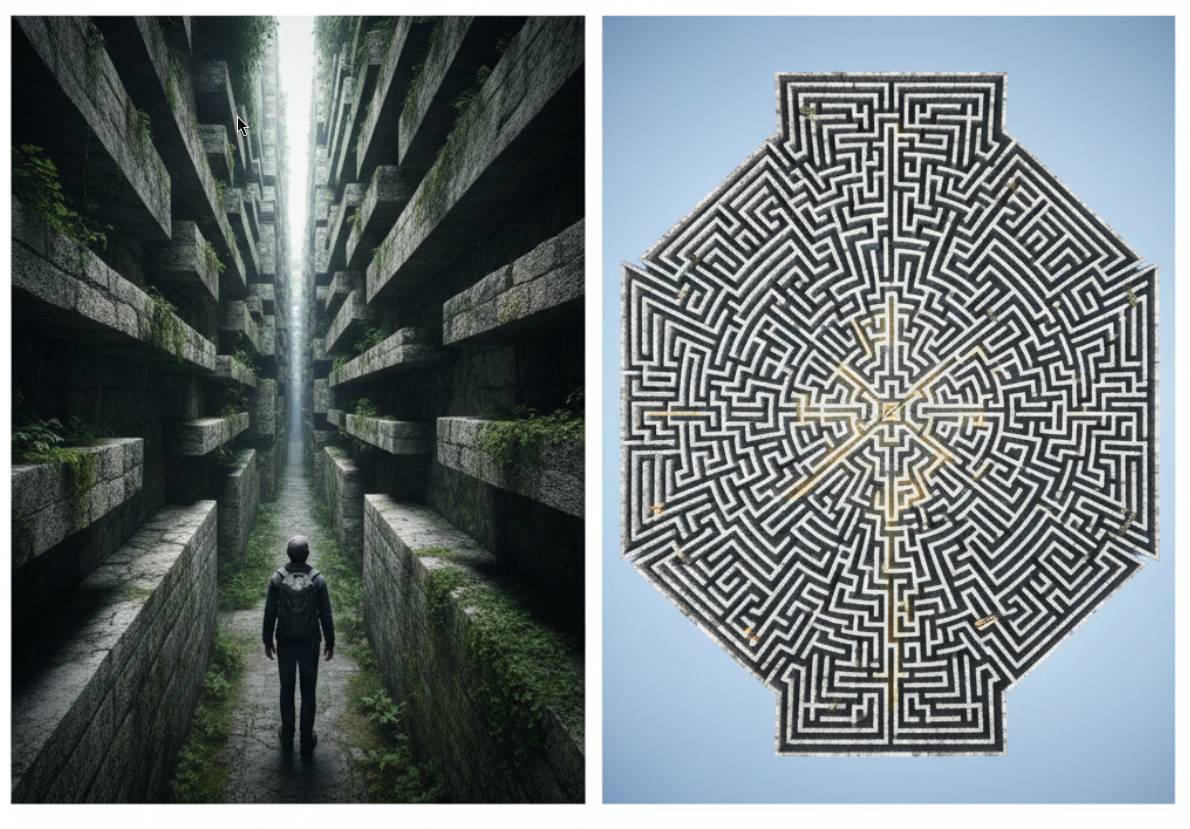

The Pattern You Can't Unsee

You saw it coming.

Not because you're smarter. Not because you have some mystical intuition. You saw it coming because you've seen it before. The architecture choice that would create scaling bottlenecks. The vendor that looked perfect on paper but would fail at the contract negotiation stage. The seemingly minor technical debt that would compound into a crisis.

You brought it up. Time and time again. "We need to address this now." "This will become critical." "I've seen this pattern before."

And time and time again, you heard the responses:

- "It'll be OK."

- "The alternative is too expensive."

- "We can't afford to stop and fix that now."

- "That seems like an edge case."

Some people nodded politely. Some debated the specifics. A few quietly distanced themselves from you—the person who always sees problems, who can't just go with the flow.

So you had a choice: fight harder or let it play out.

You chose to step back. Not out of spite. Not to prove a point. But because you knew something else from experience: until people feel the pain themselves, explanations don't stick. You can describe fire, but touching the stove teaches in a way words never can.

Weeks passed. Then months. The problem got worse, exactly as you predicted. The late nights started. The firefighting became routine. Half the team now spends half their time dealing with the cascading consequences of that initial decision.

Now they see it too.

And now they've come around. Someone needs to fix this mess. They might even ask you. Or they might not—they've found someone else, someone who doesn't carry the baggage of having been the dissenting voice.

What do you do now?

What Experience Actually Is

Before we answer that, we need to understand what just happened. Because this story isn't about intelligence or foresight in the mystical sense. It's about pattern recognition.

Experience is accumulated pattern recognition. You've seen versions of this movie before. You know how Act 2 ends because you've watched similar plots unfold. The specific details change—different tech stack, different team, different business constraints—but the underlying pattern remains consistent.

This creates a strange asymmetry. To you, the outcome is obvious. You're not predicting; you're recognizing. It's like seeing a word you know how to spell—you don't sound it out letter by letter, you just see the whole thing at once.

But to someone without that accumulated pattern library, your warnings sound like speculation. They can't see the pattern because they haven't indexed enough examples yet. They're still sounding out the letters.

This is not a failure of intelligence. A brilliant junior engineer and a mediocre senior engineer might have the same analytical capability. But the senior has a corpus of "this is what usually happens" that the junior hasn't built yet.

The gap is invisible. You can't see what patterns exist in someone else's head. And they can't see the patterns you're referencing when you raise a concern.

Why Your Warnings Failed

Let's be specific about why the warning didn't land.

You were operating from compressed intuition. You said "this will scale poorly" but what you meant was: "I've seen three architectures like this, and in two cases they hit scaling limits at around 10x growth, requiring a complete rewrite. The third case pre-optimized too early and wasted six months. Based on our growth trajectory and team size, we'll hit the pain point in about 18 months, which is too late to fix it cleanly but too early to get prioritization now."

You compressed all of that into "this will scale poorly" because to you, the whole chain of reasoning is obvious. But to someone without those three reference experiences, it sounds like vague concern.

You were asking them to trust your pattern library. Essentially: "Believe me that this pattern leads to that outcome, even though you can't verify it yourself yet." That's a huge ask. You're asking them to make a costly decision now based on your internal database of experiences they can't access.

You were fighting present urgency with future pain. The current path solves today's problem. Your warning is about a problem that doesn't exist yet. Humans are terrible at weighing future abstract pain against present concrete urgency. This isn't irrationality—it's reality. The deadline is real. The scaling problem is hypothetical.

You underestimated the social dynamics. If you're significantly more experienced than the team, your warnings might trigger defensiveness rather than curiosity. "Is this person saying I'm not capable of seeing this myself?" "Why do they think they know better than the whole team?" Experience creates authority, but authority without shared understanding creates resistance.

You didn't provide a learning path. You told them what you saw, but you didn't give them a way to see it themselves. Without that, they're either accepting on faith or rejecting based on their own analysis. And their analysis, constrained by their pattern library, led them to a different conclusion.

When Letting It Fail Is the Right Move

Here's the uncomfortable truth: sometimes the most effective teacher is consequence.

You could have fought harder. You could have escalated. You could have refused to participate in the doomed approach. And sometimes that's the right call—when the stakes are high enough, when the risk is existential, when you have the authority and social capital to force the issue.

But in many cases, forcing compliance without genuine buy-in creates worse outcomes:

They would always doubt the decision. If you had somehow convinced them to take the more expensive, time-consuming path based purely on your authority, every bump along the way would have triggered "Maybe we were wrong. Maybe we should have done it the other way." When things went wrong (and things always go wrong), they'd blame the approach rather than learning from the obstacles.

You would own the outcome forever. By forcing the decision, you'd take full ownership. Every problem, every delay, every unexpected complication would be "your" fault. The team wouldn't develop their own understanding—they'd just learn to defer to you or resent your authority.

They wouldn't learn the pattern. The point isn't to avoid this specific mistake. It's to develop the pattern recognition that prevents the entire class of mistakes. Lived experience teaches in a way that secondhand warnings cannot. The team that goes through the pain and learns from it becomes capable of seeing the next version of this problem themselves.

You would become the bottleneck. If the team only makes good decisions when you intervene, you've made yourself a permanent dependency. Scaling yourself means enabling others to develop their own pattern recognition.

So you let it fail. Not out of vindictiveness. Not to prove a point. But because you recognized that this particular failure, at this particular scale, was survivable—and the learning it would generate was valuable.

That's the calculus of experience: knowing which failures to prevent and which to allow.

Now They See It

The fires are burning. The team is exhausted. The problem you predicted is now the problem they live with daily.

And they've come around. They see it now. They understand what you were warning about.

This is the moment where you have the most leverage—and where you must be most careful.

The wrong response: "I told you so."

It's tempting. You were right. You warned them. They didn't listen. Now they're suffering the consequences.

But "I told you so" achieves nothing except satisfying your ego. It doesn't repair the problem. It doesn't build trust. It doesn't help them develop better judgment next time. It just makes you feel superior while making them feel smaller.

Worse, it makes you the problem. Instead of the team learning "we should have addressed this earlier," they learn "this is the person who rubs it in your face when you're wrong." That reputation will ensure your next warning lands even worse.

The wrong response: Bitterness.

Maybe they didn't choose you to fix it. Maybe they brought in someone else—a consultant, a new hire, someone who doesn't carry the history of having been the dissenting voice.

This stings. You saw it coming. You could have prevented it. Now someone else gets to be the hero who fixes it, while you're stuck with the reputation of being the person who "always sees problems but doesn't solve them."

But bitterness poisons you more than them. And it ignores something important: maybe you're not the right person to fix it. Not because you lack the skills, but because the social dynamics are too complicated now. Sometimes a fresh perspective really is more effective than a vindicated critic.

The right response: Partnership in learning.

The team has now earned the pattern. They didn't have it before—they couldn't see what you saw. Now they do. They've paid the tuition in late nights and firefighting.

Your job is to help them consolidate that learning into durable pattern recognition. Not to claim credit. Not to assert authority. But to help them extract the maximum value from this painful experience.

Building the Bridge

Here's how you move forward:

For the experienced person (you):

1. Name the pattern, don't claim credit.

When discussing what went wrong, focus on the underlying pattern, not your earlier warning. "This is a common pattern—optimizing for short-term delivery at the cost of architectural flexibility. The question for us is: how do we recognize this trade-off earlier next time?"

Not: "This is exactly what I said would happen."

2. Share your reasoning process, not just conclusions.

Now that they can see the outcome, walk them backwards through how you spotted it early. "When I see X architecture decision, I check for Y scaling assumption. In the three times I've seen this pattern before, here's how it played out..."

You're not showing off your pattern library. You're teaching them to build their own.

3. Acknowledge what they saw that you didn't.

Because here's the thing: they probably made trade-offs that did work. Maybe they shipped faster. Maybe they learned things about the problem space that justified the approach in the short term. Maybe the business context you weren't fully considering made their path rational.

Experience creates pattern recognition, but it can also create pattern over-matching—seeing problems that aren't actually there, or being too conservative. The less experienced team might have valid reasons you're not weighing correctly.

4. Offer to help, but don't demand it.

If they want your help fixing the problem, make yourself available. If they've chosen a different path or different people, respect that. Your goal is long-term team capability, not short-term vindication.

For the less experienced person:

1. Recognize experience as a real asset.

When someone significantly more experienced raises a concern you can't verify, treat it seriously even if you can't see the pattern yet. You don't have to defer automatically, but you should engage deeply.

Ask: "Can you help me understand what pattern you're seeing? What are the reference cases?" Not to challenge their authority, but to learn their reasoning.

2. Distinguish between "I can't see the problem" and "there is no problem."

These are different statements. The first is honest humility about the limits of your pattern library. The second is overconfidence in your current visibility.

You can disagree with experienced people. Sometimes they're wrong—pattern-matching to the wrong reference class, or being too conservative. But make sure you're disagreeing based on analysis, not just because you can't see what they see.

3. Build explicit learning loops.

When you do choose to go against experienced advice, make it a learning opportunity: "We're going to try path A instead of path B. Let's document the concerns now, and in 6 months we'll review how it played out."

This transforms disagreement from social conflict into collaborative experimentation.

4. When you were wrong, say it.

If the experienced person's warning turned out to be correct, acknowledge it directly. "You called this, and we should have weighted your concern more heavily. Help me understand what you were seeing that I couldn't see yet."

This isn't admitting defeat. It's extracting maximum learning from the experience.

For the team:

1. Create space for "future pain" conversations.

Build processes that force consideration of long-term consequences. Architecture review meetings. Retrospectives that look at decisions from 6 months ago. Written decision documents that make reasoning explicit.

These processes help bridge the gap between people operating from different pattern libraries.

2. Treat experience as a skill, not a hierarchy.

Experience is real. It's valuable. It's also not the only input that matters. Frame it as "accumulated pattern recognition" rather than "authority." This makes it discussable rather than something you either defer to or reject.

3. Build shared context explicitly.

When experienced people compress their intuition into brief warnings, create space to decompress it. "Walk us through the reference cases. What are the conditions under which this pattern applies? What are the alternatives you've seen work?"

When less experienced people question the warning, encourage that—but as exploration, not rejection. "What would we need to see to validate this concern earlier?"

4. Distinguish between "learning failure" and "existential failure."

Some failures are tolerable learning opportunities. Some are company-ending disasters. Make that distinction explicit. For learning failures, it's reasonable to try the less experienced path and learn from consequences. For existential failures, experience should carry more weight.

The Gift You Can't Give Directly

Here's the paradox of experience: the most valuable thing you've gained—your pattern library, your intuition, your ability to see around corners—is precisely the thing you can't transfer directly.

You can describe the patterns. You can walk through the reasoning. You can warn about consequences. But until someone has lived through enough instances themselves, they can't truly see what you see.

This is frustrating. You watch people make mistakes you could have prevented. You see them learn lessons you already paid for. You feel the weight of knowledge that others don't value because they can't verify it yet.

But this is also where humility enters. Because you were once that person. You didn't believe the warnings either, until you lived through the consequences. Your pattern library was built on your mistakes, not someone else's wisdom.

The bridge between experience levels isn't built by the experienced person demanding deference. It's built by creating environments where pattern recognition can be shared, questioned, tested, and accumulated.

What You Do Now

So back to the original question: They've finally come around. The problem you warned about is now the crisis they're living. What do you do now?

You help.

Not to prove you were right. Not to claim vindication. Not even to fix the immediate problem, necessarily.

You help them consolidate the learning. You name the pattern so they can recognize it next time. You share your reasoning process so they can build their own. You acknowledge what they saw that you missed. You treat this as a team that's now closer in pattern recognition than before, not as a hierarchy of right and wrong.

Because the real gift of experience isn't being right about what's coming. It's helping others develop the ability to see it themselves.

The gap between experience levels is real. It's significant. It creates genuine communication challenges and strategic disagreements.

But it's not unbridgeable.

Every senior person was once junior. Every pattern you now see instantly was once invisible to you. The difference is just time and accumulated reference cases.

The question isn't whether experience matters—it does. The question is whether we can create environments where that experience becomes shared capability rather than isolated authority.

Where the experienced person doesn't have to choose between "fighting harder" and "letting them fail."

Where the less experienced person doesn't have to choose between "blind deference" and "learning everything the hard way."

Where teams build collective pattern recognition rather than depending on the wisdom of whoever's been around longest.

That's the bridge.

And building it is harder than being right, more valuable than vindication, and more important than any single technical decision.

The pattern you see might be invisible to others. That's the burden of experience.

But helping others learn to see it—that's the gift.